By Nina Lagpacan Originally published by the Trust-Based Philanthropy Project on May 9, 2023.

In early 2020, Oceankind started our trust-based philanthropy (TBP) journey and, like many other funders, took a deeper look at how we could be better grantmakers and better partners to our grantees in response to COVID, our country’s racial reckoning and the murder of George Floyd.

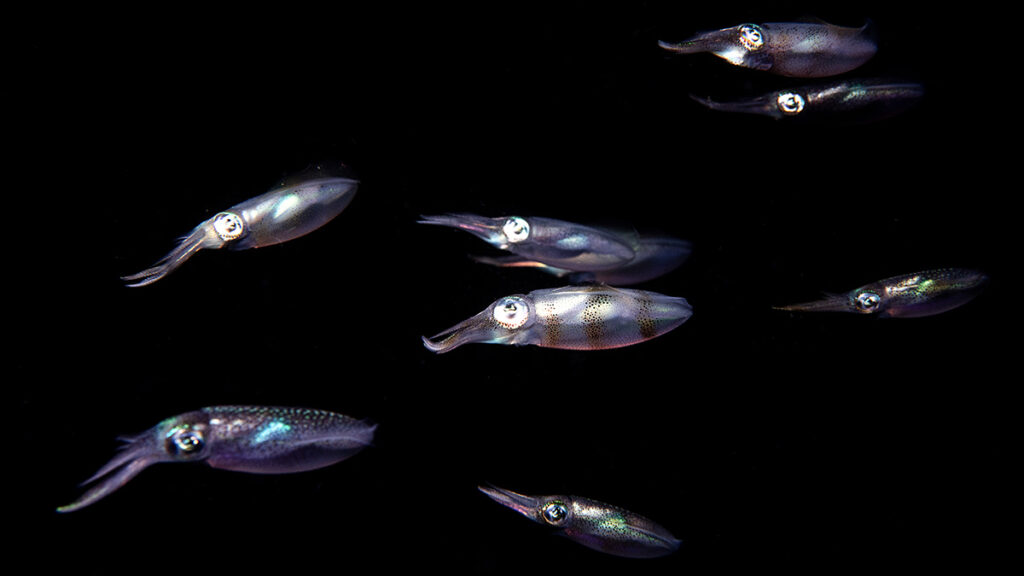

Oceankind is a relatively new funder, founded in 2017, focused on ocean health and marine conservation. Many TBP principles were embedded in Oceankind’s values from the onset, but the six practices framework of TBP has helped us become more intentional about embedding equity into our grantmaking practices.

OceanImageBank / Gregory Piper

Getting Flexible with Flexible Funding

There is a lot of nuance that can be explored with this practice, especially if your foundation’s policies and/or values restrict giving multi-year, general operating support (GOS) grants. Even with program and project support grants, there are still ways to build in flexibility that can support more trust-based and transparent relationships.

In fact, not all Oceankind relationships start with a multi-year, GOS grant—it’s common for grants with new partners to be smaller grant awards and for a shorter duration, such as 12–18 months. We’ve found that sometimes the best way to learn about a new topic or a new relationship is to provide a small, low-risk grant and measure success through internal learning objectives rather than conservation outcomes. This “learn by doing” attitude has allowed program officers to explore new topics or focus areas within our broader portfolio.

For example, when we wanted to better understand how impact investments could further ocean conservation, we made 12-month grants to three accelerator programs. Our objective was to learn alongside these grantee partners about ocean-focused investments and how to excite other investors. After our 12-month experiment, we were able to strengthen our knowledge of this space, and subsequently made multi-year, flexible grants to the accelerator programs that felt most aligned with our portfolio.

In addition to multi-year general operating grants, we do issue program and project support grants—but with lots of flexibility built in. At the outset of the grant, we communicate transparently with grantees that they can let us know if their timelines or deliverables need to shift within the grant term. We let them know that we trust them to pivot and make adaptive decisions. This goes a long way in both cultivating mutual trust and improving nonprofits’ ability to advance their conservation goals.

Most importantly, multi-year and flexible support has enabled our grantees to build organizational capacity making them more effective in pursuing conservation goals. Azul is a good example where our flexible support has enabled the organization to build communication and development capacity. Their Executive Director has more time to focus on program strategy, organizational growth, and elevating their leadership in the ocean justice space.

Flexible support has allowed some grantees to expand their work into emerging areas of interest. We’ve seen this with our partners at ELAW (Environmental Law Alliance Worldwide), where flexible funding has allowed the organization to expand its scope to support public interest lawyers working on marine and coastal issues around the world.

OceanImageBank / GregoryPiper

Doing the Homework (and Being Transparent) in Pre-Proposal Stages

Doing the homework is certainly more art than science. Overall, this practice encourages funders to proactively explore and research prospective grantees. Our level of due diligence is right-sized to match the grant size—a $3M investment requires much more time to scope and research than a $100k investment.

We approach our due diligence process as a series of reference checks with the organization’s permission. We will spend most of our time learning about a new organization through conversations with other funders and partners while keeping the organization updated on our due diligence progress. We are open to reviewing existing materials in various formats whether they are written strategy documents, recordings of past webinars or YouTube videos.

Most importantly, we try to minimize paperwork in the early stages of grant development and only ask for tailored materials when the likelihood of funding becomes more certain. For example, in early stages of consideration, we’ll use proposals submitted to other funders , and the program officer considering the grant will fill in missing information verbally during a team meeting. We also take good care to be transparent with prospective grantees about our grantmaking process, and are proactive in communicating about whether or not their organization is a good fit for funding. We don’t want to waste anyone’s time.

OceanImageBank / Gregory Piper

Reducing Grantee Burden Via Verbal Reporting

Over time, Oceankind has simplified reporting requirements. For example, we don’t require narrative reports—only financial reports. Moreover, releasing subsequent payments for multi-year grants is not contingent on receiving reports. Many grantees still prepare narrative reports (usually for other funders), and we’re more than happy to review those, but they’re not required.

In lieu of narrative reports, we have verbal check-ins with grantees. The frequency of those check-ins is agreed upon by the grantee and program officer at the start of the grant term. We recognize verbal check-ins can also be burdensome to grantees, so we try to right-size the frequency of check-ins to the grant size. We’ll check-in more frequently with grantees who receive multi-year, multi-million dollar awards but might only check in twice a year with grantees who receive smaller awards.

Highlights from grantee check-ins are shared through an internal weekly newsletter that’s shared with all Oceankind staff. We commit to reading the newsletter and encourage everyone to make comments directly in the shared document to keep ourselves accountable. In addition, program officers update progress on grant-specific targets and outcomes in our monitoring and evaluation system every four months.

CoralReefImageBank / Tracey Jennings

A Culture of Soliciting and Acting on Feedback

We aim to solicit feedback from our grantees in our regular communications, but we also recognize the need to create an opportunity for our grantees to provide anonymous feedback. Soliciting feedback from grantees doesn’t have to be complicated—and can be done without lengthy surveys conducted by outside consultants.

Oceankind started sending an annual survey to grantees in 2021. Our response rate has been between 55% and 70% in the two years we’ve administered a survey. It is a great way for us to get a temperature check on what we’re doing well as grantmakers and what could be improved. The survey is a Google form with eight questions and takes less than 10 minutes to complete. We aggregate the responses and pull out common themes, and make shifts to our work based on those themes.

Some of the changes we’ve made based on grantee feedback include: revising our proposal instructions and developing email templates to clarify the grant development process and expectations for timing, removing the non-disclosure agreement requirement, and providing clarity around our relationship with the donor advised fund we work with.

OceanImageBank / Cinzia Osele Bismarck

Offering Support Beyond the Check

This is an area for growth for Oceankind. We’re six program staff with limited capacity, but we are exploring ways to provide additional organizational development support for our grantees. We often end our grantee check-in conversations by asking grantees, “What else can Oceankind do to help?”. Grantees usually respond to this question with requests for introductions to certain funders, other grantees in our portfolio, and good consultants who can help them with a short-term need or additional funding requests for things like translation services or conference support. I can’t think of a request that we have denied and are glad that grantees feel empowered and comfortable enough with Oceankind staff to even ask – this could well be a result of implementing trust-based philanthropy practices 😉

The Benefits of Trust-Based Philanthropy

Ultimately, our commitment to trust-based philanthropy has allowed us to build authentic relationships with grantees. It’s enabled us to have candid conversations and understand the challenges our grantees are facing. It’s allowed us to think big picture alongside our grantees about the needs and gaps in the ocean conservation field.

It has also been really rewarding to receive direct, positive feedback from our partners about how our shifts in practice are helping them achieve their mission in a more effective and efficient way:

“Support from Oceankind overall has been a blessing—the gifts help us make a meaningful impact for our waters, and the lack of burdensome paperwork and reporting makes it easy to work effectively to fulfill our mission with Oceankind’s support.”

“We have a true partnership with Oceankind, and through that are able to candidly share what is working, what is not working and where we may need additional support or input. We find Oceankind to be continuously open to these types of conversations and extremely knowledgeable about our work.”

This all sounds great, but let’s take a moment to be transparent about some of the challenges. Practically speaking, multi-year support ties up future grantmaking budgets and leaves less room to scope new areas of interest. As a result, our programs are shifting to maintaining existing relationships leaving less room to support new organizations and leaders.

It’s also become clear that TBP, as a means to be a more equitable grantmaker, isn’t a compelling reason for everyone to change their grant-making practices. Others may find efficiency arguments or a desire to become a better grantmaker, partner, or colleague more promising reasons to implement trust-based practices. Whatever the reason or motivation, the most important thing is to start implementing TBP to reduce the burden on grantees and shift power from grantmakers to grant seekers.

OceanImageBank / Amanda Cotton

Final Words of Advice

I’m grateful that Oceankind has been able to test the waters, pun intended, in practicing the six practices of trust-based philanthropy but let me leave you with some final words of wisdom.

There’s no one size fits all approach to implementing the six practices of TBP. You have to find a way to implement that works best for your foundation. For Oceankind, we’re not 100% a trust-based funder in terms of how we do our grantmaking; we recognize that Oceankind staff still hold a lot of power in making funding decisions and setting program strategies. We see trust-based practices as one set of tools in our grant-making toolbox, and we’re on a journey to understand which practices make the most sense for us as we continue to strive to support our partners.

Whatever the reason or motivation, the most important thing is to start implementing trust-based philanthropy to reduce the burden on grantees and shift power from grantmakers to grant seekers. And it doesn’t have to be a big lift—you don’t need 100% buy-in from senior leadership or your board to start. There are pieces of trust-based philanthropy that you can implement in your individual grantmaking, whether that’s how you show up in a relationship with grantees or taking it a step further and experimenting with a small set of long-standing, “trusted” (ha) grantees.

There are ways to support TBP even if your foundation isn’t amenable to changing grant-making practices. We support re-grantors that are pushing trust-based practices even further than what Oceankind is comfortable with at this stage. I’ve learned alongside our partners at Justice Outside and a participatory grantmaking pooled fund, Mosaic, about how their grant-making approaches reduce the burden on grantees and shift decision-making power and authority to grantees. I’m sure you can find a transformational regrantor that aligns with your foundation’s mission.

There’s room for creativity in shaping your TBP practice, but the important thing is to start.

TBP Practices to Start Today

The TL;DR version of how to start implementing trust-based practices:

- Build flexibility into program and project support grants if multi-year, unrestricted funding isn’t possible.

- Start with a one-year, small grant to a new potential grantee. Assess the relationship after a year and make a multi-year, less restrictive grant if appropriate. Be transparent throughout the relationship to manage expectations of future funding.

- Invest time to research and learn about potential grantees. Put the onus on grantmakers to conduct thorough due diligence.

- Accept existing materials like proposals submitted to other funders as concept notes or letters of interest. Hold off on asking grantees to complete a full proposal until your likelihood of funding is closer to 100%.

- Give grantees the option of verbal check-ins in lieu of narrative reports.

- Develop internal systems to capture and share grant progress with relevant stakeholders.

- Be responsive to grant applicants. Provide frequent status updates about your proposal review process and be swift in letting them know if the answer is no.

- Send a simple annual survey to grantees to solicit anonymous feedback. Take the feedback seriously and make reasonable changes to grant-making practices based on the feedback.

- Listen for ways you can provide non-monetary support. Ask grantees, “How can I help?”